Insight: Citadel’s New Home in South Florida

Tidal Flooding in Miami at Brickell Bay Drive and 12th Street, looking Southeast October 2016. The future Citadel tower site (approximate outline shown in red) is the parking lot at the left of the image

Executive Summary

Citadel, one of the world’s largest hedge funds, plans to build a $1 billion supertall mixed-use tower along the Miami waterfront for its new global headquarters - attracted, like many other financial firms, by Florida's low tax burdens.

South Florida has historically been prone to rising seas and storms, made worse due to the increasing effects of climate change. Existing defenses against floods and storms are inadequate for current and future events, with even moderately effective improvements estimated to cost billions.

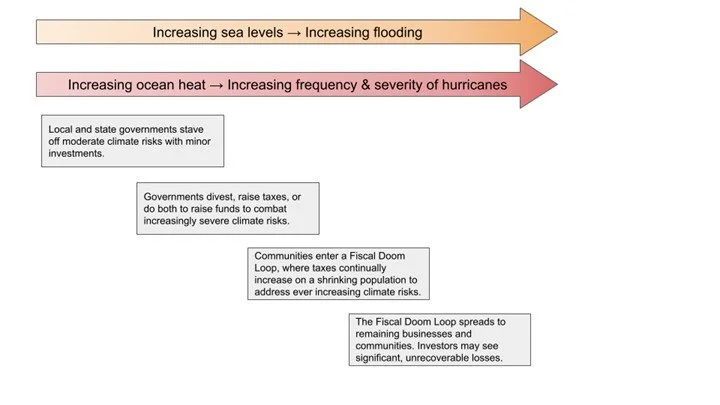

A Doom Loop could form for Citadel Tower and other Miami property investments:

As climate risks continue to drive up insurance costs and force higher taxes, cuts to public services may occur, prompting residents and businesses to leave. Falling rents and property values could lead to stricter lending terms, with lenders demanding more equity and lower DSCR thresholds.

Rather than double down on a failing asset, Citadel (and its LP’s) may abandon the tower rather than add equity to a property with little hope of rebounding value.

Given the increasing frequency and severity of flooding and tropical storms in this region, investing today into real assets here raises some questions:

Can a fiduciary put LP capital to work on the Miami waterfront today? What type of downside protections are in place?

Can a bank responsibly lend on this project? What downside protections are in place? Do they believe the tower will stay in the black with increasing insurance rates? Do they believe that tenants will want to occupy the building for decades into the future?

Will Florida’s tax advantages erode under the state’s growing burden of climate infrastructure needs? If so, will this shift occur in the short term or the long term?

What does the exit strategy and timeline for a financial firm entering Miami today look like?

A Doom Loop for Miami due to increasing ocean head and sea levels would affect the city’s future businesses and communities, including the recently arrived Citadel

Background

Citadel LLC, which manages approximately $63.4 billion in hedge fund assets, and its market-making arm, Citadel Securities, with around $80 billion in assets, is planning to develop a 1.7 million-square-foot mixed-use tower in Miami. The proposed 1049-foot skyscraper will rise 58 stories in the heart of the Brickell neighborhood—nicknamed “Wall Street South”—with office space extending from the ground floor to the 38th floor and a luxury hotel occupying floors 42 through 58. A portion of the office space will house Citadel’s future global headquarters. The tower, which will also feature a helipad at its crown, is situated directly on the waterfront facing Biscayne Bay and is expected to cost over $1 billion.

The tower site location along Biscayne Bay reportedly floods even during relatively weak Category 1 hurricanes. To address this, the new tower’s design includes upgrades to the sea walls, flood resistant doors, and its own stormwater management system.

Citadel’s rendering of its new Brickell headquarters along the Biscayne Bay waterfront, Credit: Citadel

Citadel’s rendering of its new Brickell headquarters along the Biscayne Bay waterfront, Credit: Citadel

In addition to commercial property, Citadel’s CEO Ken Griffin is investing massively in South Florida for his private use as well. Griffin acquired 27 acres in Palm Beach in 2023 and is reportedly building a $150M - $400M home on 8 of those acres in an area known as “Billionaire’s Row”. When finished, the home will reportedly be one of the most expensive in the world, at an approximate valuation of $1 billion. This would be in addition to two homes he bought in Coconut Grove and seven properties on Star Island, totaling $276 million in 2022 and 2023.

Griffin founded Citadel in Chicago in 1990 under the name Wellington Financial, which later evolved into the Citadel we know today. The plans for the tower represent the culmination of a multi-year shift to South Florida for Citadel from its Chicago roots. Citing concerns over crime and local government policies, Griffin began distancing himself from Chicago in the summer of 2022, both professionally and personally. He formalized the move with a letter to Citadel employees announcing the company's relocation, and he and his family made the move that same summer.

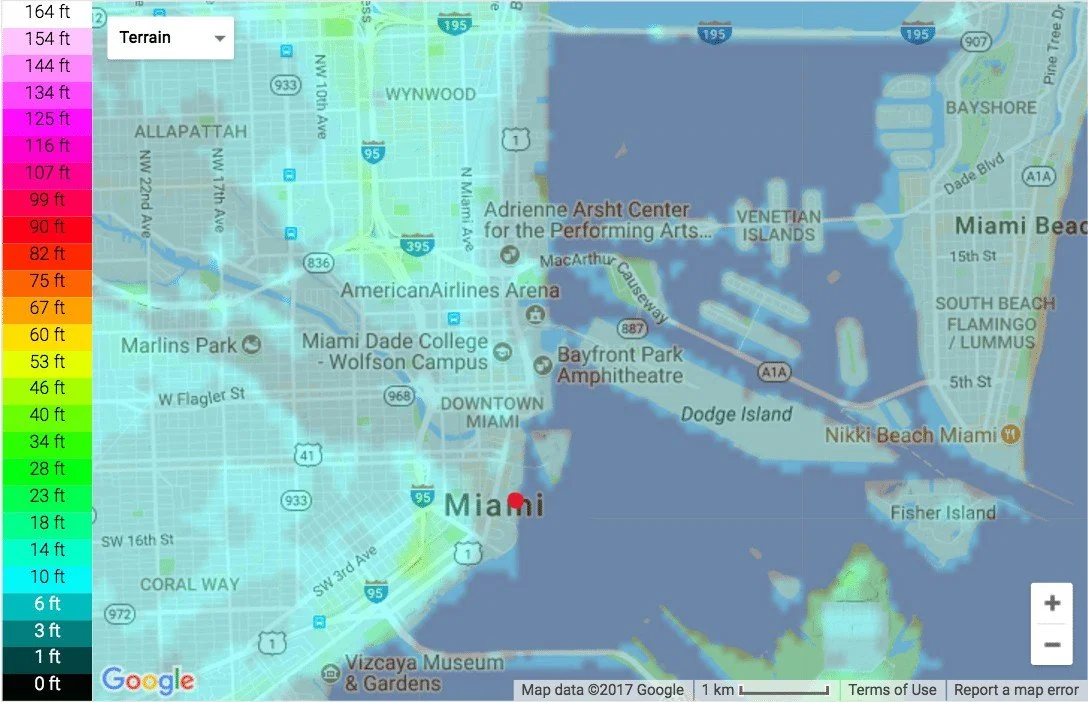

Elevation Map of Downtown Miami, Miami Beach and surrounding areas. Citadel’s proposed headquarters site is marked in red, directly on the Biscayne Bay waterfront. Credit: miamicondoinvestments.com

Downtown Miami’s Brickell neighborhood, known as “Wall Street South”. Citadel’s proposed headquarters site is marked in red. Credit: Google

Griffin’s relocation plan, while large and loud, is not alone. Numerous other financial institutions have either relocated or increased their presence in South Florida in recent years, including Goldman Sachs, Blackstone, Icahn Capital Management, and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund.

Sunshine and Low Taxes

The announcement that America’s most profitable hedge fund was leaving Chicago for Miami made financial news headlines around the world. While Florida’s sunny weather and relaxed lifestyle are often cited as reasons to relocate, the most catalyzing factor for Miami’s financial success appears to be its tax policies.

Florida’s greatest advantage over the traditional finance hubs of New York and Chicago is its lack of any state income tax. In contrast, Illinois has a flat 4.95% state income tax rate, while New York combined City and State income taxes can exceed 16%. For a pass-through entity like Citadel’s hedge fund, the lack of income tax represents significant tax savings. Florida also has no estate taxes and no capital gains tax.

Florida also advertises fewer and less aggressive regulations and oversight for hedge funds and other financial services like investment advisors. According to CNBC, Illinois and New York scored third and second to last in Business Friendliness, respectively. A separate study by Tax Foundation found Illinois became more hostile to businesses from 2018 to 2022, dropping from 29th to 36th place in the country.

A warm climate, lower taxes, and business friendliness regulations have all created a positive feedback loop for finance – wealthy individuals and businesses moving to Florida create an environment attractive for additional financial services. Henley & Partners and New World Wealth found that from 2014 to 2024 the number of millionaires in Miami nearly doubled to 39,000.

Based solely on Florida’s tax and business environment, it makes sense why fiduciaries would want to relocate to Miami from more regulated places like Chicago or New York. However, fiduciaries should not make decisions based only on tax and regulatory policies. Climate risk is a real, growing financial risk and should be part of every fiduciary’s decision framework. South Florida’s rising sea levels, tropical storms, tidal flooding, and other escalating climate risks pose material threats to real assets. In a world increasingly affected by climate volatility, tax advantages may prove fleeting if the underlying environment and its assets are repeatedly exposed to growing hazards.

Miami, Florida in January 2024. In summer 2022, Citadel relocated its headquarters to Southeast Financial Center (center, right), but is planning to move its headquarters to its new supertall tower when complete.

South Florida - A Region Plagued with Issues

Rising Sea Levels

Rising sea levels due to a warming planet have been a concern for the Miami region for decades. In March 2025, NASA released information that suggested that in 2024, the warmest year on record, sea levels rose higher than expected, primarily due to warming ocean water expansion (thermal expansion). The expected sea level rise level of 0.17 inches was surpassed by an actual rise of 0.23 inches, 35% higher than expectations.

For the City of Miami, officials must constantly update their planning efforts to reflect the latest sea level rise projections. In 2019, stormwater planners were using a 2015 estimate projecting 18 to 30 inches of sea level rise by 2070. However, a revised forecast published that same year indicated the same level of sea rise could now occur a full decade earlier - by 2060.

Tropical Storms

Miami and greater South Florida are no strangers to tropical storms from the Atlantic Ocean. Tropical storms with wind speeds of 74 mph or greater are officially considered hurricanes, and typically bring high winds, heavy precipitation, and storm surge upon making landfall. Numerous powerful hurricanes have impacted Miami over the past several decades, including Hurricane Donna (1960, Cat 4), Andrew (1992, Cat 5), Wilma (2005, Cat 5), and Irma (2017, Cat 5).

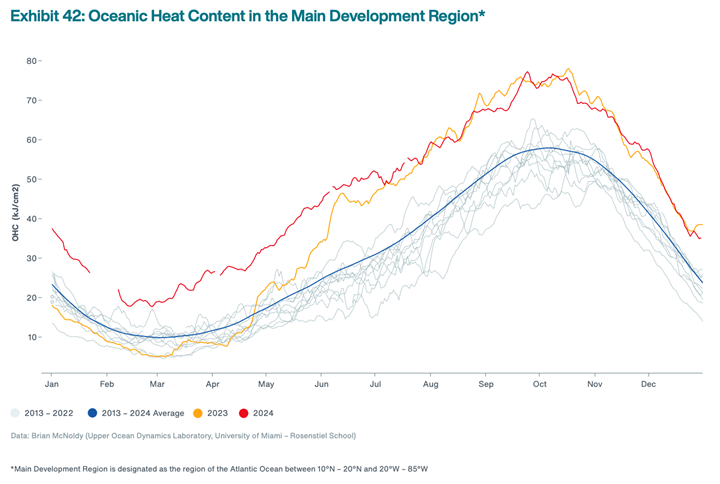

Warming oceans and higher sea levels are the perfect ingredients to make Florida’s tropical experiences go from bad to even worse. Warmer oceans provide more evaporated moisture to create stronger storms, while higher seas amplify storm surges with ever increasing amounts of water permeating upon landfall. Although in recent years the Miami region has been spared, other strong hurricanes due to warming oceans have wreaked destruction in other parts of the United States, including Hurricane Ian (2022 - Cat 5, third costliest US hurricane) Hurricane Helene (2024 – Cat 4, seventh costliest US hurricane), and Hurricane Milton (2024 – Cat 5, one of the strongest hurricanes as recorded by wind speed and low pressure). 2024 was a “hyperactive hurricane season,” with increasing ocean temperatures generating stronger and more frequent storms in recent years.

Insert caption here about Rising Ocean Heat graph

King Tides and Tidal Flooding

In addition to hurricane induced storm surges and precipitation from flooding, South Florida also experiences tidal flooding from king tides. Certain times of the year when the sun and moon are gravitationally aligned, abnormally high tides can occur known as King Tides. In Miami, king tides are known as “sunny day flooding” and occur in both the fall and spring, although they are more severe in the spring. As the sea levels continue to rise, the king tides escalate as well, and tidal floods will be able to reach neighborhoods further inland.

Saltwater Intrusion

Rising sea levels are creating problems for South Florida at the surface and underground as well. Miami’s primary drinking water source, Biscayne Aquifer, is at risk from saltwater seepage due to the rising seas and development in the Everglades. Already, other areas in Florida, such as Dania Beach and Hallandale Beach, have had their freshwater wells impacted due to saltwater intrusion.

Subsidence

A December 2024 study in the Earth and Space Science Journal by the University of Miami found significant skyscraper subsidence in the Miami area. The study identified 35 buildings across the region that are gradually settling, including several high-rise structures on the barrier islands Sunny Isles Beach, Surfside, and Bal Harbour — that have sunk by as much as 8 centimeters over the past decade. This subsidence is closely tied to the Miami area’s unique geology, which consists of porous oolite limestone, nicknamed “Miami limestone”, mixed with layers of sand. The oolite, formed from fossilized coral and other marine organisms, is especially vulnerable to processes such as creep deformation, groundwater removal during construction, and the injection of stormwater into the ground. These activities can accelerate the natural dissolution of the limestone, particularly under the weight of heavy buildings. Notably, the study found that this subsidence occurs as long as ten years after construction—contradicting earlier geotechnical assessments that predicted settling occurs only in the months after construction.

Di Lido Island as seen from Biscayne Bay, with Miami highrises in the distance

Overwhelmed Defense Systems

Climate events like king tides, hurricanes, and heavy rain events can overwhelm the city’s existing defense systems. The municipal governments have known about the issues for decades, but in recent years the accelerating effects of climate change have kept climate infrastructure in the spotlight.

In the Fall of 2017, the City of Miami passed the “Miami Forever” bond, which promised “a stronger, more resilient future for Miami” by “alleviating existing and future risks” to the city. The bond was first presented by the Mayor in 2016 but only approved by voters in 2017 after included affordable housing commitments were increased. The $400 million bond promised to invest in sea level rise and flood protection, roadways, parks and cultural facilities, public safety, and affordable housing. As of June 2024, there remained $147 million available funds in the Miami Forever Bond.

That same year, the City of Miami released an update to its Stormwater master plan, which estimated a minimum investment of $3.8B over the next 40 years to keep most of the city from flooding. Compared with the $192 million availableallocated for flood protection in the Miami Forever bond, this represents a budget shortfall of over $3.6B for the planned stormwater infrastructure improvement.

The proposed investment includes some 93 new stormwater pumps (the City currently has 13), upgrading portions of the city’s 86 miles of sea walls from 3.45 feet to 6 feet, thousands of additional stormwater injection wells, and a multi-mile system of 8 foot diameter underground pipes. Despite the hefty planned, but as yet unfunded, investments and improvements, the plan notes some sites within certain neighborhoods still need to be abandoned to allow for managed retreat, strategic stormwater retention and absorption.

The study also noted that even after the multi-billion dollar investment, the future of Miami could consist of “floating cities and converting roads to canals”. Compounding the budget challenge to planned stormwater infrastructure, the estimated $3.8 billion investment does not include the program’s engineering and administrative costs, estimated to cost tens of millions annually, nor does it include the millions of dollars needed annually to maintain the improvements.

European Precedents

To understand the scale of a large-scale flood protection endeavor as proposed by Miami’s stormwater master plan, one may look to other flood protection programs carried out in Europe.

The MOSE project (Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico), a flood barrier system completed in October 2020, protects Venice from flooding up to three meters (~ 10 feet) above sea level. After decades of planning, the impressive feat of engineering began construction in 2003, with an original cost of approximately €1.6B ($1.88B) and completion in 2011. But the project fell victim to corruption, delays, and cost overruns, and after 17 years was completed for a final cost of €5.5B ($6.1B). While the MOSE project is now complete and in operation, the system still costs €300,000 ($352K) each time it is activated. Rising sea levels also call into question the long term effectiveness of MOSE, as it was planned in a different era, and sea level rise projections have increased since then.

After two severe floods in the 1990’s, in 2007 the Dutch government launched the Room for the River program - a series of some 30+ projects optimizing river flood management. The projects included creating water buffers, levee relocation, channel modifications, flood bypass construction, and lowering flood plain levels. The program was received well overall, but there was also public backlash to certain aspects, such as demolishing homes for flood dikes or the managed retreat of historically agricultural land into flood plains. The program was fully finished in 2018, with a total cost of €2.3 billion (approximately $2.7 billion). Despite the program’s success, there exists continuing debate over the project’s maintenance, as well future protection needs. As an example, dike improvements have been historically required every 30-40 years, but with climate change impacts, the Dutch government now expects to make improvements every 14 years.

Although Miami’s plan doesn’t include any complex flood gates like the MOSE project, Venice’s experience serves as a reminder that large scale projects like this often go over schedule and budget. For a time sensitive issue like rising seas, expecting Miami’s actual implementation to adhere to its original cost and schedule may be dangerously optimistic. The Room for the River program also highlights how managed retreat, citizen opposition, and flood works maintenance can challenge even the most successfully implemented programs.

Miami, Florida in January 2024. In summer 2022, Citadel relocated its headquarters to Southeast Financial Center (center, right), but is planning to move its headquarters to its new supertall tower when complete.

Planting Roots in the face of Rising Risks

We’re not sure why Ken Griffin is investing billions of dollars in real assets in an area with increasing odds of destruction. For someone who prides themselves on risk analysis, the commitment to Miami feels less like a strategic decision and more like a Vegas roulette spin. Or perhaps Ken Griffin plans to only appear committed to a losing strategy, but has a set up for someone else to take the fall. One must wonder what the date in his head is to rush for the exit.

Sure, the state level tax benefits clearly provide a strong advantage for the health of Citadel’s business, but it’s not unreasonable to imagine those benefits may be outweighed by mounting climate-related costs. The City’s recommended $3.8 billion of flood control and sea level infrastructure investments in the coming decades can not be ignored. They may force the state and local governments to raise taxes or issue substantial bonds to fund these needs—potentially diminishing the very financial incentives that drew companies like Citadel in the first place.

By that time, the gold rush will be over, the finger pointing will begin, and we’ll know for sure whether Ken Griffin was just gambling with Miami, or knew when to exit all along and just didn’t tell anybody.

Conclusion

Despite its grandiose plans for Miami, it’s worth mentioning that Citadel is not all-in on South Florida. In addition to its Miami headquarters development, Citadel also plans to build a new 62 floor office building at 350 Park Avenue in New York City’s midtown. When asked by Bloomberg in 2024 on his outlook for the finance ecosystem in Miami and New York, Ken Griffin replied “New York is the financial capital of America today… Miami, I think, represents the future of America.” While Ken Griffin may be right about the future financial capital of America, there’s no question that the forecast for Miami’s storm impacted coast is clearly at the epicenter of actuarial climate risk and potential future destruction of real assets.

Insights

-

Stranded Asset Risk, Valuation, and Climate

Tail risks from climate change are increasing for real estate investors

-

The Feedback Loop of Healthy Sustainable Development

Growing a community the right way leads to a robust cycle

-

Lessons in Expansion from Texas Hill Country

Recent floods remind us of the dangers of risky growth